Returning to the Futaleufú

Standing below Zeta Rapid on the Futaleufú River in December 2014, my first time back in 30 years

Up until last year, I had run the Futaleufú River exactly once. A whole lot of people know a lot more about it than I do. But there are only a small group of us who knew the Futaleufú before it became THE Futaleufú. As part of the crew on the first raft expedition on the river in 1985, I had the good fortune to make its acquaintance when it was just a beautiful blue river disappearing into deep mountain gorges, near a town of the same name, in the southern mountains of Chile.

Today a person from any corner of the globe can go online and book a trip to run the Futaleufú. In 1985, the only way to be part of the very first Futaleufú trip was to be friends with Steve Currey and Dan Bolster.

Brad Lord and I were long time guiding partners with Dan and the three of us were part of Steve’s crew on Chile’s legendary Bio Bio River. We came with Steve to row four big yellow Maravia rafts down the Fu. With us were a hand picked group of adventurous clients that Steve knew from past trips with Steve Currey Expeditions.

It was February 1985. We all stood on a beach a few miles upstream from the town in the drizzling rain with only a sketchy idea of what lay downstream. The total of what we knew was from Dan and I scouting from town a year before, followed by a couple of passes flying over in a small plane. Over the next four days, the Futaleufú River would nearly take one of our lives and leave us feeling connected to it forever.

1985 was my last year of full time raft guiding. Dan and I had been working North American summers in California and South American summers in Chile for four years. After that I went off and got a job and raised a family. I was 62 years old and a completely different person when I returned to the Fu for the second time last year bringing along my wife and two grown children, all of them river guides.

The 1985 Expedition

For this first rafting expedition on the Futaleufú, we brought years of experience doing multi day rafting trips on big rivers like the Salmon, the Colorado and the Bio Bio. The whitewater stretch of the Fu was only 45 kilometers, not very long by those standards. We budgeted three days to run it from the top with fully loaded oar boats carrying camping equipment, a full kitchen, food and all of our personal cameras and gear.

If modern Fu trips carry gear at all, the most they bring is lunch. Nowadays, on many trips, the passengers stay in beautiful camps along the river in tent cabins with real beds. There are nice bathrooms with flush toilets. They soak in hot tubs with river views and eat delicious sit down meals in weatherproof comfort.

Today’s Fu guides are world-class experts, who know all the rapids. Some have guided the river for a decade or more. They carry passengers downstream in big but light and nimble rafts with a safety net of kayaks and catarafts out front. They know all the different sections of the river at different water levels.

The walls of the Fu canyon go straight up thousands of feet. Any rain in the drainage gets funneled directly into the river, which can transform overnight. At some water levels most of the river is safe and accessible but after a rain, whole sections are considered too dangerous. There are three rapids where modern outfitters never run commercial passengers at all.

Standing on the beach with our passengers in their bright raincoats, we congratulated ourselves that it wasn’t raining as hard as the day before when we couldn’t see our hands in front of our faces. We had no knowledge of weather’s effect on water levels. We had world-class big water experience, two superb safety kayakers in Eric Nies and KB Medford, and perfect boats for running huge powerful water. The serene current flowing past us on that beach gave no clue of what lay ahead.

Of the four rowers on the trip Steve was the most experienced. His father ran a rafting outfit and Steve grew up rafting. He had a quiet self-effacing way of not looking as big and strong as he really was, but he was one of the best rowers I ever saw. Unfortunately he is no longer with us. Steve passed away a few years ago.

Dan, Brad and I filled out his crew. We had received our primary big water educations from the Tuolumne River in California. We did our finishing school, on the Bio Bio, a river with the volume and power of the Grand Canyon and the technical challenges of the Tuolumne. The Bio Bio was a whitewater monster.

It was after a Bio Bio season that Dan and Steve were in a Puerto Montt hotel room pouring over topographic maps when they spotted a promising blue line inland from the tiny port of Chaiten.

The Bio Bio was under a death sentence. Its legendary rapids and the way of life in its canyon were to be drowned by massive hydroelectric dams. Steve and Dan were in search of the next great Chilean whitewater river.

So a year before the ’85 descent, three of us followed Dan’s purposeful back and long strides south to go take a look. We were the first river runners in the Fu valley. We might as well have been from Mars with our bright colored Patagonia Baggies, fleece sweaters and our loco obsession with the river. The residents with their big smiles and their homespun wool hats and coats, were equally exotic to us.

Life in Fu was like winding the clock back 50 years from the modern 1980’s to an older and simpler way of living. Buying a loaf of bread turned into an afternoon of talk over cups of tea. Chilean friends we met on the ferry pulled into town and asked the mayor, who happened to be the local butcher, if they could camp in the brand new school building. He just handed them the key. It was that kind of town. Hospitality was a way of life in this protected mountain Shangri La.

Our last night in town, we were literally taken by the elbows and ushered into a celebration at the community center and pulled into the middle of a dancing crowd of grinning dark haired locals. We towered over them with our light hair and big beards. By the end I was laughing so hard, propped against a row of wool coats hung on the wall that tears were running down my face.

The weather cleared up our first afternoon on the river. The rest of the time it rained. When we hit the first major whitewater, the Infierno Canyon, our three-day timetable went out the window.

At lower water, today this steep canyon is divided up into four distinct Class V or V+ rapids. The dripping steep forested canyon we saw in ’85 was one continuous stretch of whitewater that took us half a day to scout, bush whacking through the thick undergrowth for a mile to see its entire length. When we all arrived safely below the rapid we were in shock. The river was not as big as the Bio Bio, but the rapid had packed a more powerful punch than anything we had ever experienced. We called it “Surprise Canyon.” The boatmen looked around into each other’s eyes. We knew right then we were into something serious.

Brad Lord is and was a tough athlete and an excellent rower. It was his first season rowing in Chile. He had just handled the big Maravia raft on a high water Bio Bio trip, a significant benchmark of world rafting at that time. Where the Infierno canyon turned to the right, his boat had slid into an eddy that it took him a good 10 minutes to escape. The high water Fu was giving notice that it would be another level entirely.

Proceeding downstream we had to keep scouting major rapids while our time schedule kept crumbling and putting us under pressure to move as fast as we could.

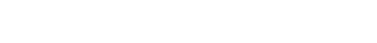

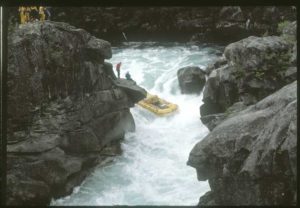

We had lost a half-day scouting Infierno Canyon, which was nothing compared to the 24 hours we spent solving Zeta, the first of the rapids that does not get run by modern outfitters. We had a few moments of despair as we made a makeshift camp on the cobble above the zig zag where the river drops two stories through a throat of bedrock. All we wanted was to get the people and boats through safely. We ended up launching the rafts through the rapid unmanned. But to reach that point all the dangerous complications had to be addressed one by one. It wasn’t till the next day that we could put all the pieces in place to get us on our way downstream.

The first boat through Zeta on the Futaleufú

It seems amazing that we spent only about an hour looking at and successfully running Throne Room, the second rapid that never gets run with passengers these days. The only casualty was one of Brad’s yellow Carlisle oars busted in half.

That night we were worn down. We had been worried for days and hadn’t slept well at Zeta. Every ounce of our energy was going to keeping everyone safe through the rapids. The passengers were grumbling about the lousy camps. We were feeding them great meals and doing all the camp work like on any commercial river trip, while trying to make them believe everything was normal. Privately we were very focused. Our passengers were not exactly blissful, but they were ignorant to the extreme risk in what we were doing.

At dusk, when we were just serving dinner, four riders galloped on horseback into camp. Steve’s driver and some local ranchers had come to see why we were over a day late for our rendezvous. He gave us the bad news that the big rapid we were anticipating, now called Terminator, was not far downstream.

Looking at low water Terminator January 2016.

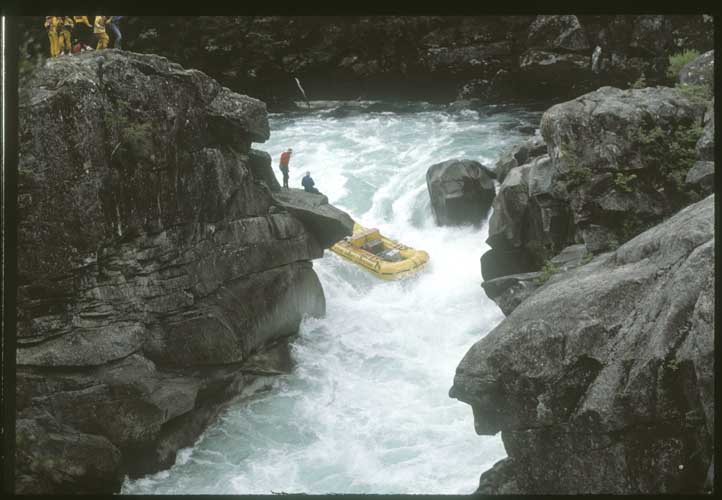

So on our fourth rainy morning after another wet night we spent interminable hours examining every inch of Terminator. This was the third of the rapids where even at lower water passengers are walked around by trail. We also had made the decision to walk our passengers, and so it was just the guides who returned to the rafts tied in the eddy above the giant rapid. Face to face, there was real honest doubt about whether we should even attempt it. A tiny mistake at the top would have dire consequences below.

Which was exactly how it happened. Brad’s boat swung a little wide while maneuvering at the set up, and ended up a couple of feet too far right. The huge rafts and their heavy plywood floors had run everything the river had thrown at us to this point. But you could never for a second let them pick up steam on a wrong course. They were hard to turn, let alone in huge water and they ran like a freight train in the direction they were pointed.

It was literally a matter of 24 inches or so in that pressure cooker situation that sent three of us into a route down the left side of the rapid and Brad down the right toward a cavernous hole in the surface of the river. His plunge into it, and his subsequent swim are captured on video. They are epic. Without a good life jacket and dry suit he would not have made it. For a few excruciating moments all of us—including Brad—didn’t think he would.

The raft stayed in the hole for 30 minutes while the river stripped it clean. After Brad was rescued the next thing we saw floating downstream, were ¾ inch plywood decks ripped to pieces like cardboard.

When the boat finally kicked free, Brad and our driver chased it down with the truck and managed to recover it. Already days behind schedule and all safe and in one piece, we decided we had done enough. Negotiating a night in the shelter of a pig barn, we called it a trip and packed the truck the next day with anything but a sense of disappointment. We had more than survived a remarkable river. Four boats had rowed it nearly flawlessly down to a margin of about 2 feet on one of the most impressive rafting rapids on earth.

Postscript

Our trip would be the only raft descent of the Fu in the 1980’s. In March 1991, future outfitter, Eric Hertz, mounted a descent that included Steve and former Olympic kayaker Chris Spelius as a safety boater. His party rafted the entire length of the river with only the extremely risky Zeta portaged— and Steve got the chance to finally row the final 7 miles of the Futaleufú.

Dan and Steve’s vision came true. The Fu did become the next great Chilean rafting river, a world class and world famous whitewater destination.

It should be noted that there were kayak descents of the river dating back to 1985. Spelius led groups of paddlers down in the late 1980’s and his descents were instrumental in opening up the Fu to commercial boating. Since that time generations of guides and outfitters have made it safe and accessible to any who still seek a truly wild and beautiful place.

The irony of this story is that we scouted the Fu to replace the threatened Bio Bio, and now the Fu is itself in serious jeopardy of being dammed. No matter how many battles are won, a free flowing river is never completely safe.

Late last year, we were all heartened to hear that Endesa, Chile’s largest energy company, had punted plans to build dams on the river. But the company still has the water rights, and recently requested a change in location, which legal experts suggest could be a move to re-activate the project. In response, the community is forming a new coalition to denounce plans to dam the Futaleufú and argue for local determination of Futaleufú’s future.

The goal is for the Futaleufú to receive permanent protection under Chilean and international law, a feat that Futaleufú Riverkeeper’s International Director, Patrick Lynch, says could take years to achieve and will require coordination at all levels.

Standing on the bank of the Fu thirty years later, I see a place in the world that is still only partially tamed. It remains dangerous and wild. Rafting it today with one of the excellent outfitters, we can touch and feel this wildness. The sparkling walls of aquamarine water rise up to bury the rafts. The guides expertly weave the boats past the danger, but the edge is never far away. They are focused and their hearts still pound.

At the bottom of Terminator, my two kids and I tasted the wildness when our raft drifted a few feet off its line. A powerful Fu wave blasted us into the water. We reviewed it in slow motion on a GoPro video and it happens in the blink of an eye.

Rescue boats were right there to pick us up, close to the same place where Brad was rescued 30 years ago. The Fu was having a little chuckle at our expense and reminding us of our place in the order of things. A much-needed reminder on a fast changing planet we need to save one wild place at a time, one special river at a time.